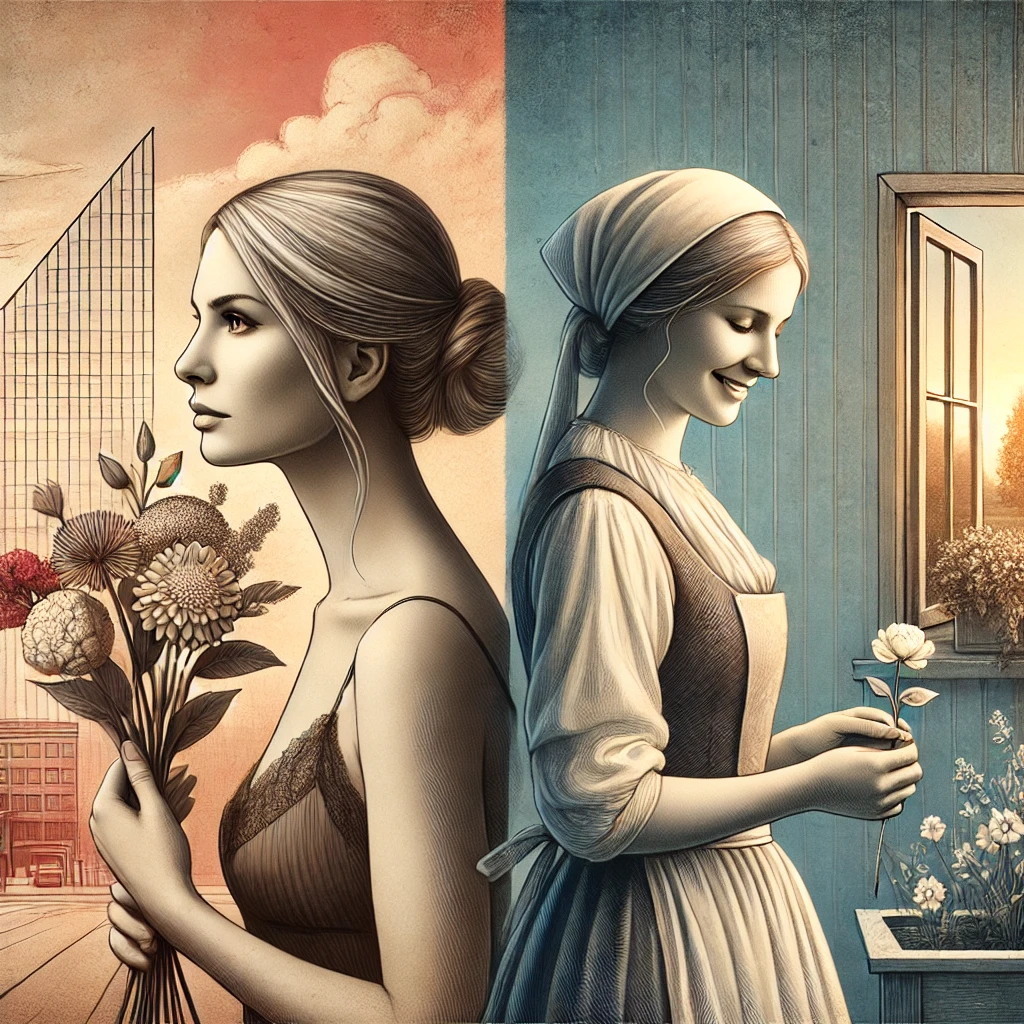

The Differences Between a Woman Who Wants a Husband and a Woman Who Wants to Be a Wife

The dynamics of modern relationships are increasingly complex, influenced by societal shifts in gender roles, expectations, and personal values. In the context of marriage, two distinct perspectives often emerge: the desire for a husband versus the desire to be a wife. While these may appear similar on the surface, they represent fundamentally different approaches to partnership and commitment. This article explores these differences and their implications for modern relationships.

1. Motivation for Commitment

A woman who wants a husband may be primarily motivated by the idea of companionship, societal status, or achieving a particular milestone in life. Her focus might center on what a husband can bring to her life—financial stability, emotional support, or social recognition. Conversely, a woman who wants to be a wife often emphasizes the role she seeks to fulfill within a relationship. Her motivation stems from a desire to nurture, build a partnership, and invest in the growth of the marital union.

Research on marital satisfaction suggests that intrinsic motivations, such as personal fulfillment and mutual support, are stronger predictors of long-term happiness than extrinsic factors like societal pressure or financial security (Amato, 2010). This underscores the importance of aligning motivations with the relational roles each partner seeks to embody.

2. Expectations of the Relationship

The expectations held by a woman who wants a husband may be more externally focused, often shaped by cultural norms or personal ideals of what a husband “should” provide. For instance, these expectations might include financial provision, protection, or fulfilling a traditional role within the family unit.

In contrast, a woman who wants to be a wife often adopts a more internally driven perspective. She focuses on what she can contribute to the relationship, such as emotional support, shared responsibilities, and fostering mutual respect. This aligns with the concept of communal orientation in relationships, where the emphasis is on meeting the partner’s needs without expecting direct reciprocation (Clark & Mills, 2012).

3. Approach to Challenges

When challenges arise, the difference in perspective becomes particularly evident. A woman seeking a husband may evaluate problems in terms of what she is or isn’t receiving from her partner. If unmet expectations dominate her perception, it can lead to dissatisfaction or conflict.

Conversely, a woman who desires to be a wife is more likely to approach challenges collaboratively, viewing them as opportunities to strengthen the relationship. This aligns with findings that couples who adopt a team-oriented mindset are better equipped to navigate conflict and maintain marital satisfaction (Markman, Stanley, & Blumberg, 2010).

4. Role of Personal Identity

For a woman who wants a husband, her identity may be intertwined with the social or cultural validation that comes with marriage. The title of “wife” may hold less intrinsic value than the societal perception of being married.

However, a woman who wants to be a wife typically views the role as an extension of her personal identity and values. She may find meaning in the responsibilities and commitments that come with the role, emphasizing personal growth and the deepening of emotional connections within the marriage.

5. Long-Term Compatibility

The difference between wanting a husband and wanting to be a wife has profound implications for long-term compatibility. Relationships built on the former may face challenges if external expectations are not met or if the relationship is not rooted in mutual understanding and shared goals. By contrast, relationships centered on the latter are more likely to thrive, as both partners invest in the well-being of the partnership, prioritizing collaboration over individual expectations.

Studies have shown that marital satisfaction is highest when both partners exhibit high levels of commitment and engage in behaviors that promote mutual trust and respect (Fowers & Olson, 1993). This suggests that aligning relationship goals and motivations is critical for a successful marriage.

Conclusion

The distinction between wanting a husband and wanting to be a wife reflects deeper differences in motivations, expectations, and approaches to relationships. While both perspectives can lead to fulfilling partnerships, understanding and aligning these differences is essential for building a resilient and harmonious marriage. Ultimately, the key lies in fostering a relationship based on shared values, mutual respect, and a commitment to growing together.

References

Amato, P. R. (2010). Research on divorce: Continuing trends and new developments. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 650-666. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00723.x

Clark, M. S., & Mills, J. (2012). A theory of communal (and exchange) relationships. In P. Van Lange, A. Kruglanski, & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology (pp. 232-250). Sage.

Fowers, B. J., & Olson, D. H. (1993). ENRICH marital satisfaction scale: A brief research and clinical tool. Journal of Family Psychology, 7(2), 176-185. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.7.2.176

Markman, H. J., Stanley, S. M., & Blumberg, S. L. (2010). Fighting for your marriage: A deluxe revised edition of the classic best-seller for enhancing marriage and preventing divorce. Jossey-Bass.