Have You Ever Thought You Forgave Someone Only to Find Out You Hadn’t? Understanding Forgiveness and Its Complex Layers

Forgiveness is often considered a vital step toward emotional healing, allowing individuals to release resentment and move forward. However, many people experience situations where they believe they have forgiven someone, only to later realize that the lingering feelings of hurt and resentment suggest otherwise. This phenomenon highlights the complexity of forgiveness, revealing that it may not be as straightforward as it initially seems. The purpose of this article is to explore the nature of forgiveness, the reasons why individuals might struggle with genuine forgiveness, and the implications of unfinished forgiveness on mental health and well-being.

Understanding Forgiveness

Forgiveness is typically defined as a conscious, deliberate decision to release feelings of resentment or vengeance toward a person or group who has harmed you, regardless of whether they actually deserve it (American Psychological Association, 2023). Research on forgiveness indicates that it involves both cognitive and emotional processes, meaning it isn’t just about letting go mentally; it also involves genuine emotional healing (Enright & Fitzgibbons, 2015).

Forgiveness can be separated into two main types: decisional forgiveness and emotional forgiveness (Worthington, 2006). Decisional forgiveness is the conscious decision to forgive someone and act as if the hurt no longer impacts the relationship. Emotional forgiveness, however, involves truly letting go of the negative feelings and emotional responses associated with the hurt. It is possible for an individual to experience decisional forgiveness without achieving emotional forgiveness, which can explain why some people believe they have forgiven someone only to later realize that they haven’t fully done so.

Why Forgiveness Can Be Difficult to Fully Achieve

There are several reasons why genuine forgiveness may be challenging to accomplish. Some of the most common factors include the following:

1. Residual Resentment: Even after making a decision to forgive, individuals may still hold on to lingering negative feelings. Research by McCullough et al. (2003) suggests that emotional forgiveness is a gradual process that unfolds over time, rather than an instant event. Unresolved anger, sadness, or betrayal can resurface, especially when triggered by related events or memories.

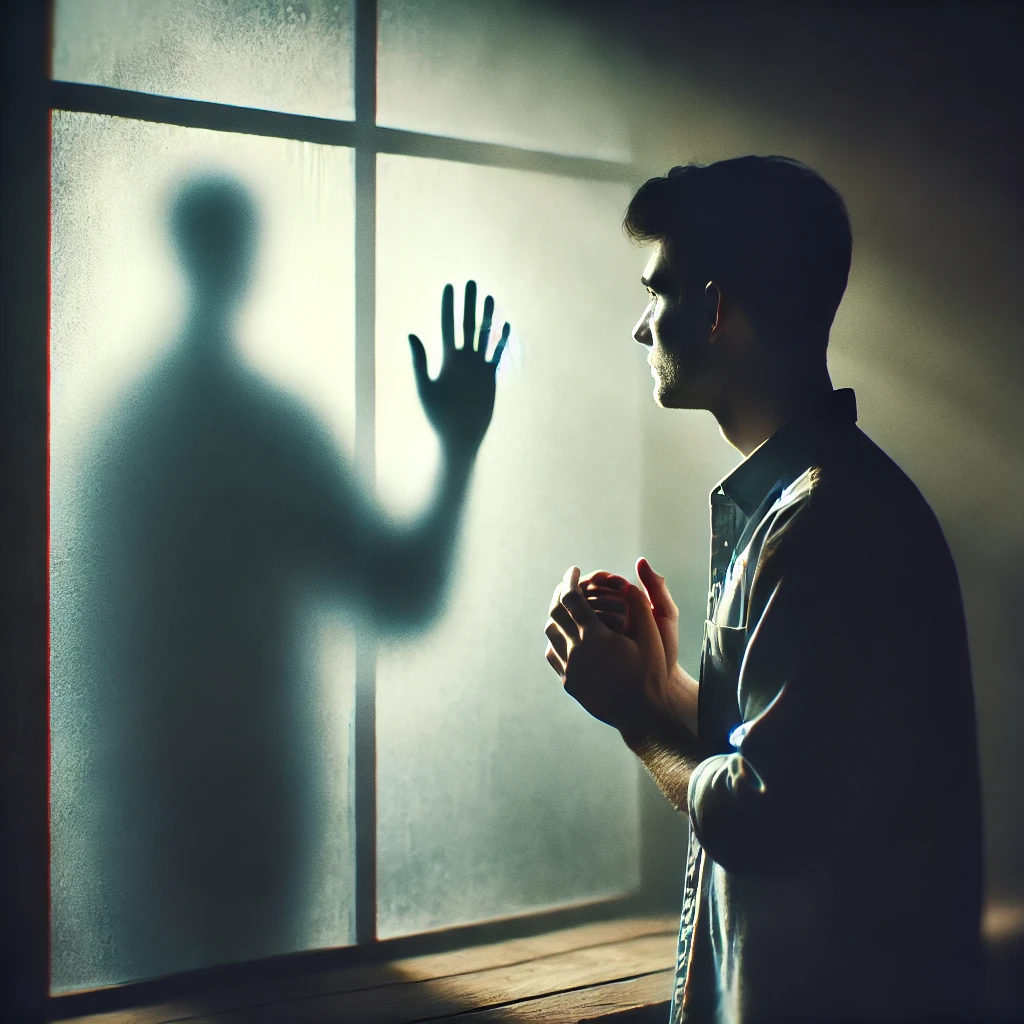

2. Self-Protection Mechanisms: For some individuals, holding onto resentment serves as a psychological defense mechanism to prevent future harm. By not fully forgiving, individuals may feel they are protecting themselves from further hurt (Wade, Hoyt, & Worthington, 2014). In this sense, forgiveness might feel like vulnerability, as it involves letting go of a protective barrier against potential future pain.

3. Mistrust and Lack of Reconciliation: Forgiveness does not necessarily mean reconciliation. When the person who caused harm has not taken responsibility, offered an apology, or changed their behavior, individuals may find it difficult to move toward true emotional forgiveness (Exline & Baumeister, 2000). The absence of reconciliation can lead to doubts about forgiveness, as it feels unfinished or insincere without mutual effort.

4. Reliving Past Trauma: Certain offenses may be tied to deeper emotional wounds or traumas. If the original hurt triggered past trauma, forgiving can be even more difficult because it involves working through multiple layers of pain. Research indicates that people who have experienced significant trauma often struggle with forgiveness, as unresolved trauma complicates the healing process (Toussaint, Worthington, & Williams, 2015).

5. Expectations and Idealized Forgiveness: Cultural and religious beliefs often encourage forgiveness as a moral or spiritual obligation, creating pressure to forgive quickly or completely (Enright & Fitzgibbons, 2015). However, when individuals try to “force” forgiveness due to external expectations rather than genuine emotional readiness, they may mistake the decision for actual healing. Over time, this dissonance between expectation and reality can become evident, revealing incomplete forgiveness.

Signs of Unfinished Forgiveness

Realizing that one has not truly forgiven can manifest in various ways. Some common signs include:

• Ruminating on the Hurt: When individuals continue to think about the offense or replay events in their minds, it may be a sign that forgiveness has not been fully achieved. Persistent rumination indicates unresolved emotional processing, suggesting that genuine forgiveness has not yet been reached (Toussaint et al., 2015).

• Negative Emotional Triggers: Experiencing anger, sadness, or resentment when thinking about the person or event can indicate unfinished forgiveness. Emotional triggers often reveal hidden feelings that were not addressed in the initial forgiveness decision (McCullough et al., 2003).

• Difficulty in Maintaining Positive Interactions: Struggling to feel positively toward the person involved or finding it challenging to engage in meaningful interactions can indicate that forgiveness remains incomplete (Wade et al., 2014). True forgiveness often includes an element of goodwill or empathy toward the other person, even if reconciliation is not achieved.

Strategies for Genuine Forgiveness

For those who realize they have not fully forgiven, several approaches can help facilitate emotional forgiveness:

1. Self-Compassion and Patience: Allowing oneself to feel and process emotions without judgment is essential. Genuine forgiveness is not a quick process; it requires patience and self-compassion (Worthington, 2006).

2. Therapeutic Support: Therapy can provide a safe space to explore lingering emotions, especially for those dealing with trauma-related forgiveness struggles. Techniques such as cognitive-behavioral therapy and forgiveness therapy can aid in processing and releasing negative emotions (Enright & Fitzgibbons, 2015).

3. Practicing Empathy and Perspective-Taking: Research shows that empathy can promote forgiveness by helping individuals understand the other person’s motivations and perspectives (McCullough et al., 2003). This does not excuse harmful behavior but can foster emotional release.

4. Journaling and Reflective Exercises: Writing about feelings, thoughts, and experiences related to the offense can help bring clarity to unfinished forgiveness. This process can encourage emotional expression and insight, paving the way for genuine forgiveness (Toussaint et al., 2015).

Conclusion

The journey toward forgiveness is complex and personal. Many people believe they have forgiven, only to later discover that deeper emotions remain unresolved. Recognizing this experience is an important step in the healing process. Genuine forgiveness requires emotional processing, self-compassion, and, at times, professional support. While decisional forgiveness may happen quickly, emotional forgiveness is often a gradual, layered experience that unfolds over time. By acknowledging the intricacies of forgiveness, individuals can work toward authentic emotional healing and peace.

This article has been written by John S. Collier, MSW, LCSW. Mr. Collier has over 25 years experience in the social work field. He currently serves as the executive director and provider for outpatient services at Southeast Kentucky Behavioral health based out of London Kentucky. He may be reached at 606-657-0532 extension 10 one or by email at john@sekybh.com

References

American Psychological Association. (2023). Forgiveness. Retrieved from APA Dictionary of Psychology.

Enright, R. D., & Fitzgibbons, R. P. (2015). Forgiveness Therapy: An Empirical Guide for Resolving Anger and Restoring Hope. American Psychological Association.

Exline, J. J., & Baumeister, R. F. (2000). Expressing forgiveness and repentance: Benefits and barriers. In M. E. McCullough, K. I. Pargament, & C. E. Thoresen (Eds.), Forgiveness: Theory, Research, and Practice (pp. 133–155). Guilford Press.

McCullough, M. E., Worthington, E. L., & Rachal, K. C. (2003). Interpersonal forgiveness in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(2), 321–336.

Toussaint, L., Worthington, E. L., & Williams, D. R. (2015). Forgiveness and Health: Scientific Evidence and Theories Relating Forgiveness to Better Health. Springer.

Wade, N. G., Hoyt, W. T., & Worthington, E. L. (2014). Forgiveness interventions: A meta-analytic review of individual and group applications. Counseling Psychology Quarterly, 27(4), 431–452.

Worthington, E. L. (2006). Forgiving and Reconciling: Bridges to Wholeness and Hope. InterVarsity Press.